Consumer Health

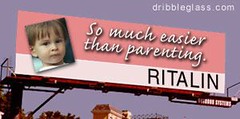

Ped Med: When to just say no to ADHD drugs

By Lidia Wasowicz Apr 26, 2006, 23:30

SAN FRANCISCO, CA, United States (UPI) -- It takes skill, experience and a certain amount of luck to know when to fold them and when to hold them in the high-stakes gamble of treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity with drugs.

Virtually everyone agrees not every child diagnosed with the disorder needs to be medicated, but how to pick out the exception has been a matter of fierce debate.

The treatment criteria call for moderate to severe symptoms that both parents and teachers agree disrupt home life and impair school performance. Yet, medication may not suit even a youngster who fits the description to a 'T.'

'We have lots of options,' noted Donna Palumbo, associate professor of neurology and pediatrics, director of the Strong Neurology ADHD Program and head of pediatric neuropsychology training at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry in Rochester, N.Y.

'Some work beautifully for some children but not for others,' said Palumbo, who is leading a four-year, federally funded study of the viability and appropriateness of ADHD diagnosis and treatment in preschoolers. 'We don`t know what works for what child ahead of time. There are lots of things to try, including non-medication treatment.'

In a consensus statement, the National Institutes of Health, the nation`s medical research behemoth, noted, 'Experts disagree on the best approaches to treating ADHD -- medication, behavioral therapy or a combination.'

All sides concur no single treatment is the answer for every child, and much thought, reflection, observation and careful consideration of personal needs and family history should precede a prescription for a course of action.

'You should be skeptical if a doctor or therapist diagnoses ADHD at the first visit and immediately prescribes a drug,' the advocacy group Consumers Union warned in a comprehensive analysis of ADHD drug treatments.

With insurance-coverage restrictions and managed-care limits tightening the constraints on a doctor`s time and reimbursed treasure, critics contend too often it may be too tempting for physicians to reach for that prescription pad prematurely -- or exclusively.

Popular fears of an over-reliance on drugs notwithstanding, the medical mainstream stands by its mainstay of pharmaceutical solutions.

Respected professional journals are devoid of evidence that would convict doctors of the massive overmedicating charged by skeptics, these specialists assert. If anything, they see a criminal neglect of youngsters who struggle needlessly when quick and easy help awaits in a capsule.

They say the power of stimulants to produce often dramatic results was established by 1997 when scientists at McMaster University in Canada concluded from an analysis of 92 studies the drugs could change behavior in some 70 percent of their users.

Two years later, what many regard as a watershed survey evaluated the safety and relative effectiveness of the leading ADHD treatments in 579 elementary school children ages 7 to 9 for up to 14 months.

The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD, or MTA, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, indicated pharmaceuticals trump non-drug options for speedily alleviating the core symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsiveness, inattention and aggression. But it acknowledged more than a pill is needed to address such overarching problems as arrested academic achievement, poor social skills or conflict at home or school.

Those challenges appeared better served with a combined approach that supplemented medication with teacher consultations, 27 group and eight individual behavioral training sessions for parents and an eight-week intensive summer program aimed at boosting the child`s social, sports and scholastic skills.

All four treatment strategies -- chemicals, talk therapy, both together, and standard care -- brought some relief. The difference lay in degree.

Children receiving managed medication and pharmaceuticals paired with psychotherapy made greater strides than the other two groups. Drugs proved superior for squelching standard symptoms. The combined package worked best in broader areas, including anxiety, oppositional disorder, social and parent struggles and classroom failings.

But just as in the race between the tortoise and the hare, the gap began to close during the second-year, a follow-up study found. By then, the groups that had made the greatest headway started to lose steam, and its gains began to dwindle.

With a shortage of even short-term studies comparing all treatment options and with the chronic disorder often persisting for many years, the results underscore the need for a scientifically sound assessment of how long, and how well, the cornucopia of ADHD treatments works, the authors said.

The MTA findings that strictly supervised stimulant use bested community care, which relied on methylphenidate (the main ingredient in Ritalin) in 68 percent of cases but under a less watchful eye, underscore the critical importance of proper monitoring of medicated children, the investigators said.

The authors noted despite 'public concerns regarding stimulant treatment, wide variations in treatment practices, and lack of evidence to guide long-term treatments of this chronic disorder,' theirs was the first systemic comparison of options to last longer than four months.

'The MTA is considered the gold standard treatment study for ADHD,' Palumbo said.

Even so, the survey has been nearly as much criticized as cited.

Detractors like psychiatrist Dr. Peter Breggin contend the stimulant-showcasing results were skewed because, among other flaws, the study lacked a comparison group of untreated children, included participants who already had shown a successful response to the drugs, failed to measure adverse effects, which most of the subjects experienced, and lacked a 'double-blind' design. Such a setup is considered a key element of rigorous research.

Rather than being kept in the dark to minimize the possibility of biased assessments, parents and teachers knew in advance whether the children they were evaluating were taking the medication that was supposed to help them.

Next: Getting a non-drug fix.

--

UPI Consumer Health welcomes comments on this column. E-mail: lwasowicz@upi.com

No comments:

Post a Comment