Drugs that promote red blood cell production and stimulants typically used to treat attention deficit disorder relieve excessive tiredness in cancer patients, according to a new systematic review of studies.

Undergoing cancer treatment can affect physical, mental and emotional well-being, and a variety of contributing factors - such as treatment regimens, psychological distress and the effects of the cancer itself - can cause cancer-related fatigue.

'Fatigue is difficult to treat as it usually has a number of contributory causes - many of which are not fully understood,' said lead investigator Dr Oliver Minton. Patients and professionals alike may consider tiredness as an unavoidable part of cancer treatment, Minton said, rather than a problem to recognise and address.

Among other therapies, drugs can improve some symptoms of fatigue in patients, said Minton, a clinical researcher at St. George's University of London.

The review analysed 27 studies of 6,746 participants that examined the effectiveness of certain drugs for relieving symptoms of cancer-related fatigue.

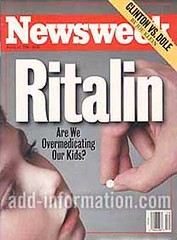

The investigators evaluated existing randomised controlled trials of (1) methylphenidate (Ritalin), a stimulant medication typically used to treat attention deficit disorders and concentration problems; (2) erythropoietin and darbepoietin, drugs used to treat anaemia induced by chemotherapy; (3) paroxetine (Paxil), a medicine used to treat depression and anxiety disorders; and (4) progestational steroids, a type of hormone therapy used to treat cancer.

The review appears in the latest issue of The Cochrane Library, a publication of The Cochrane Collaboration, an international organisation that evaluates medical research. Systematic reviews draw evidence-based conclusions about medical practice after considering both the content and quality of existing medical trials on a topic.

When it came to treating fatigue, the effectiveness of the evaluated medications varied widely.

'We found that drugs which improve anaemia caused by chemotherapy [also] improve fatigue,' Minton said.

In 14 studies, taking erythropoietin or darbepoietin proved more effective than usual care or placebo in relieving patients' cancer-related fatigue. However, Minton said that the risk or occurrence of side effects, such as aggravating hypertension and blood clots that can lodge in the lungs, brain, kidney or gastrointestinal tract, might limit the use of these drugs.

Although they appear promising, patients should also keep in mind that 'the erythropoietin findings apply only to cancer patients with anaemia,' not to all cancer patients, said David Spiegel, M.D., psychiatrist and professor at Stanford University School of Medicine. He had no affiliation with the review research.

Minton and his team also found two studies with preliminary evidence for an improvement in cancer-related fatigue with the use of the psychostimulant methylphenidate.

This finding for psychostimulants is an interesting one, because such drugs can be helpful, but they can also create dependency, Spiegel said. Furthermore, the reviewers say that additional studies are required to confirm this evidence and to assess potential side effects.

The existing research also showed that paroxetine and progestational steroids failed to improve symptoms of tiredness. As a result, the authors say that no evidence exists to support their use for the treatment of cancer-related fatigue.

As for the optimum fatigue treatment, it is still unclear, Minton said. There is little consensus among researchers on how to measure fatigue, which makes gauging the effects of medication difficult, the authors say.

Although it is common, cancer-related fatigue is difficult to treat effectively for all patients all of the time. 'The review looked at one area of treatment using drugs, but exercise and psychological interventions may also help,' Minton said.

The most important message for patients is to be aware of the effects of fatigue, and how they can affect everyday life, such as reading, self-care and daily activities, Minton said.

'If patients start to experience these problems having been pre-warned then it may reduce the distress associated with fatigue. It is worth discussing the expected symptoms and possible treatment options with your doctors before, during and after any treatment ends.

Patients can experience fatigue at the time of diagnosis, on treatment and in patients with more advanced disease. It can also occur after treatment - even when they are free of cancer. There may be options for treating it at all of these stages,' Minton said.

2 comments:

Hmmm...

Not sure if I buy this line Charles - a kid with cancer is not the same story as a kid with ADHD.

The cancer treatment itself vs. a bit of speed to keep them lively - doesn't seem like as big of a deal. It's like giving a kid opiates - if they're in chronic pain, it's pretty hard to stop from giving them the drugs.

The millions of other kids being juiced up are a more clear cut example of a system over medicating its children in order to keep humanity under authoritarian control. The same people busting teens for smoking joints are making sure the others are getting their crank on the other end. However, your conflagration of the ritalin issue with cancer patients makes it a much more murky situation and should not take back from your main views.

It does seems surprising that amphetamines would really help in the actual recovery rates, but if patients feel this drug helps them surmount the chemotherapy effects, god help anyone who would try to keep it from them.

However, judging by the amount of fighting cancer patients had to do to get marijuana legalized back in the day, I doubt this spontaneous new use for this drug is about anything except dollars and control.

yeah, cancer and ADD are very different issues.

Post a Comment